We discussed theories of inflation and whether inflation is necessarily bad for the economy in the Part 1 of the inflation debate. Recently the US Federal Reserve (Fed) stepped-up its fight against inflation after consumer prices increased by 8.7%. On June 15, 2022, The Fed announced the highest hike since 1994, in response to rising consumer prices. The pandemic-related imbalances in supply and demand, rising energy prices, and other pricing pressures all contribute to the continued high inflation rate.

Here, in Part 2, we attempt to discuss the adverse effects of a hike in the interest rate. The Federal Reserve's Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) sets U.S. monetary policy. FOMC comprises seven board members and five Reserve Bank presidents who direct open market operations that set U.S. monetary policy. One of the dual mandates of the FOMC is to maintain price stability, the other being maximum sustainable employment. Price stability means inflation remains low (close to 2% per annum) and stable over the long run. Although it is hard to set an exact numerical target for the level of employment, FOMC members estimate to keep the unemployment rate at around 4.1%.

EMPIRICAL BACKGROUND

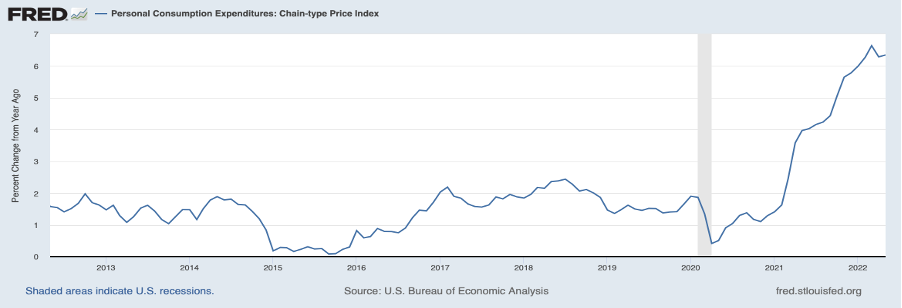

The Federal Reserve uses the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCEPI) to measure inflation. The PCEPI measures the prices people in the United States, or those buying on their behalf, pay for goods and services. The change in the PCEPI is known for capturing inflation (or deflation) across a wide range of consumer expenses and reflecting changes in consumer behavior. As we can see in Graph 1, the PCEPI grew from 1.41% in January 2021 to almost 6% in January 2022. In May 2022, the PCEPI increased 0.6 percent month over month in the US, compared to a 0.2 percent gain in April. Despite reaching a new high of 6.6 percent in March, the yearly rate remained constant at 6.3 percent. In April, energy prices rose by 35.8%, while food inflation accelerated to 11% from 10%. Core PCEPI, which excludes changes in consumer energy costs and many consumers' food prices, was 4.9 percent over the same period. These statistics show that food and energy prices were the main drivers of inflation.

Graph 1: Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCEPI)

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

In light of the rising inflation, several advanced countries like New Zealand, Canada, and Australia have increased their policy rates by 50 basis points. The European Central Bank (ECB) said it would raise interest rates in July. These countries also hinted that additional, more aggressive tightening might be required to handle inflation risks. Hence, the Fed followed the suit of advanced countries and went ahead with tightening monetary policy.

RECENT INFLATION THEORIES

The mainstream claims that rising rates will bring price stability. This is an outcome of the central bank signaling that it is taking an inflation fighting stance, thus meaning agents will stop expecting prices to rise. Additionally, the rise in rates, according to the Taylor rule, causes a fall in the demand gap (potential output demand minus current output) - if current output demanded is higher than potential output, inflation is expected. Potential output like the inflation target and the natural rate of unemployment, is yet another theoretical and arbitrary unobservable. The latter reasoning is predicated on the following flawed conception. Firstly, the quantity of investment (and consequently consumption via the determination of savings in the loanable funds market) and money demanded is an inverse monotonic function of the interest rates (Cohen & Harcourt 2003; Leroy and Cooley 1981; Kaldor 1982). This was coupled with the empirically invalid Phillips Curve (Wray 2019), to determine the general price level, which is a positive monotonic function of employment. Thus the price of high employment is inflation. In this line of reasoning, a hike in the interest rate together with cuts in fiscal spending in this model causes a reduction of employment and thus a fall in the general price level. The central banker’s defense for concerning themselves with only the impact of rising wages on inflation and not that of rising profits is that profits are reinvested and thus results in an increasing supply to meet increasing demand. However, this assumes that all profits are invested in capital assets which need not be true. Profits that make their way into financial assets cause further increases in the returns to financial instruments which discourages production (investment) and thus does not result in an increase in supply to match increases in demand, i.e. increase in demand is translated into price increases instead of quantity increases.

Another response to profits being inflationary is provided by Ilhan Dögüs's article which discusses the role of industrial organization and market power in explaining current inflation. They argue that the level of capital intensity of production, in the economy, determines how much of the increased aggregate demand translates into price changes (inflation) and how much translates into quantity changes. The premise is that capital intensive industries run with a higher level of excess capacity, since it is relatively difficult to expand this capacity. Meaning that they are more inclined to increase quantities produced in response to increased demand - to economize on fixed cost per unit. On the other hand, labor intensive industries run with less excess capacity, and are thus more inclined to react to an increase in demand with increased prices and markups (and thus inflation). This is because variable costs are a higher share than fixed costs, which means that unit costs increase with output, and thus variable costs are what are cut. Thus, the industries’ whose unit costs decrease with an increase in output optimize on costs by increasing quantity produced, while the industries for whom unit costs increase with an increase in output raise prices. Thus, the latter is more likely to contribute to inflation.

As Harvey puts it, “ There is never a good reason to stop growing prices when they are an unavoidable result of a thriving economy or what we refer to as demand-pull inflation.” The Fed felt compelled to intervene each time it appeared that wages could increase due to the increasing demand for workers. Rising prices in the US are not being driven by excess economic growth; the current predicament is considerably worse than this. Low unemployment rates at best makes a small contribution. It is blatantly apparent that the majority of price problems in the US are being caused by supply side issues (Nersisyan & Wray 2022). As Harvey noted, unless a 10% decrease in our salaries results in a >10% decline in their pricing, it will leave the US in a worse position than before. Since the demand for gas and food is price inelastic (i.e., consumer basic necessity and won’t be able to cut back that much irrespective of increase in price), a fall in income will not be matched by a like or fall in prices, most likely not.

IMPLICATIONS OF RATE HIKES

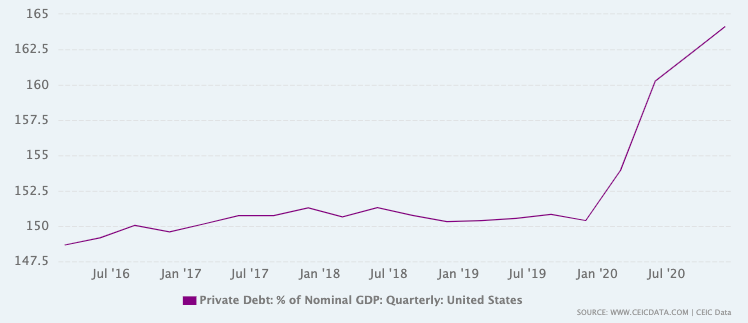

The interest rate is not only an unreliable tool to fight inflation. It also has some serious financial repercussions. Firstly, there is a concern how increase in interest rate affects debt structures. The hikes will raise the debt service of the private sector relative to their expected inflow. Private debt relative to income is higher than it has been since 2016 (refer to Graph 2). Thus, the hike could further push up the level of debt and increase defaults. It is also likely that the interest rate hike will encourage investment in industries with lower debt-service relative to inflows, thus arbitrarily redistributing profits and production. Minsky warned us that many units would turn Ponzi, i.e. be unable to meet interest or principal payment and could also have negative net worth, with hikes. Thus, resulting in a transformation into a fragile economic system.

Graph 2: USA Private Debt (in terms of percentage of Nominal GDP)

Source: CEIC Data

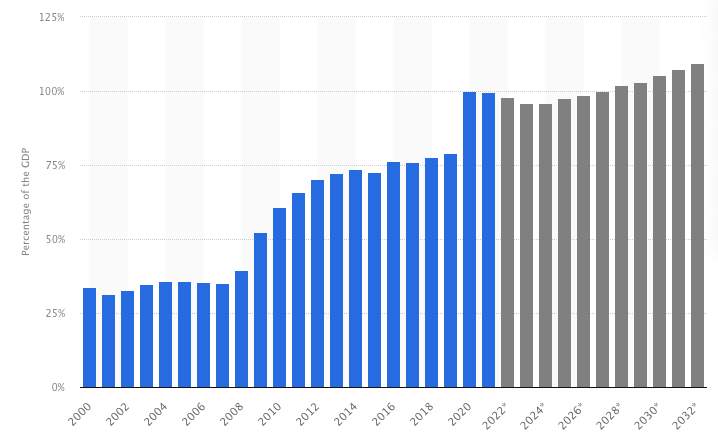

Financial intermediaries who lend mostly fixed interest and long-term loans will struggle to fund their positions in these loans, with borrowing costs rising relative to what they will earn. This will, as it has in the past during the monetarist era, result in dangerous innovations to fund or package and sell these loans - such as securitization. Such actions give agents (mostly funds and money managers) a false sense of security, since these securities are provided credit enhancements and often backed by big financial intermediators. They provide the illusion of an asset with high liquidity and at the same time a high rate of return. Third, we also have to worry about the government's volume of interest payments injected into the economy. This injection, like government transfers, will increase purchasing power and thus make inflation more likely. Public debt levels are the highest since 2000, so interest payment injections will be high.

Graph 3: US Public Debt held by the Public, forecast from 2000 to 2032

(In terms of percentage of GDP)

Source: Statista

Interest is also an input cost so prices would rise from the supply side, forcing firms to push up their mark-ups in response to higher non-wage costs. It will distort relative prices. Industries where interest is a larger share of costs would see a higher increase in price. All hikes will push pressure on workers by causing unemployment—rationing consumption through income instead of prices. The increase in rates will reduce new investment and decrease economic activity. This results in taking away from wages, and returning as interest payments. Thus, clearly favoring wealth owners.

Implications of rate hikes to international monetary theory and economic development is outside the scope of this article. However, it is evident that the hike in interest rates by the US will adversely affect development. This is because, already on account of uncertainties of COVID, investors have a high weight for liquidity, with the most liquid asset being US denominated assets and financial instruments. Adding to sharp increases in interest rates will result in massive capital inflows to the US, and increased outflows from the developing world. Thus, hindering finance required for their development. Reversals in capital flows can cause austerity and crisis in the developing world. With its inhabitants tightening belts and shifting focusing to exports to repay debt commitments (given the appreciation of the US Dollar), thus forgoing the long-term goals of development.

As Levy Economics Institute scholars (Papadimitriou & Wray, 2021) said, “The Fed continues FLYING BLIND.” It's time for a new inflation strategy beyond simply "jacking up interest rates." That outdated strategy will cause us to enter another recession. Part 1 covers alternate safer tools to fight inflation, if the inflation is indeed ‘bad.’